I’ve been wanting to write something about Explorer for a long time. The more that contemplative exploration games like Proteus, Dear Esther and Fract become an established thing, the more interesting this little (read: absolutely gigantic) 1986 game seems to become.

Explorer was created for the ZX Spectrum by UK coders Graham Relf and Simon Dunstan (under the software development wing of George Stone, one of the men behind Max Headroom). The premise is that your spaceship has crash-landed on an alien jungle planet and broken into bits, which have in turn scattered themselves across the entire globe (somehow). You have to explore and find them all. And there’s some serious exploring to do, because the game has 40 billion procedurally-generated “graphic locations” (in the marketing terminology of the time).

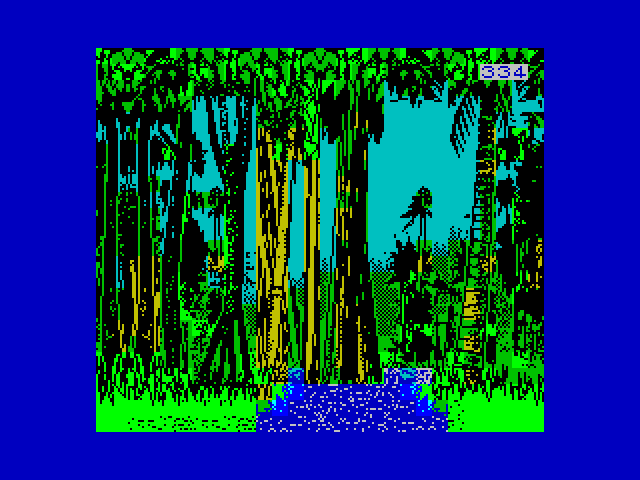

Look at one of those locations, and there’s something interesting about Explorer that’s hiding in plain sight: it’s in first-person. That’s no mean feat for the mid-’80s. It’s all smoke and mirrors, of course: 8-bit computers would have wept actual blood trying to build Explorer’s world in actual full-on 3D. Relf and Dunstan’s ‘Rotovision’ layered flat layer upon flat layer, generating static (and slow to draw) views of your immediate and distant surroundings.

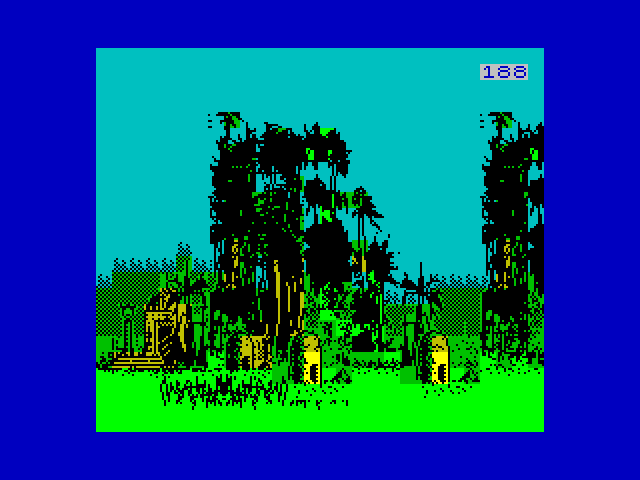

The Lords of Midnight had pioneered a similar technique. But Explorer didn’t ape the clean, two-colour, comic book style world of Mike Singleton’s masterpiece. Instead, it took a step towards realistic first-person environments. The impressionist sense of scale and distance was unusual for the time, and even now there’s a painterly quality to the environments and their use of silhouette and shading. Those trees, in particular, are somehow simultaneously a bit of a mess (mostly thanks to the Spectrum’s colour clash) and surprisingly evocative of a real jungle towering over you.

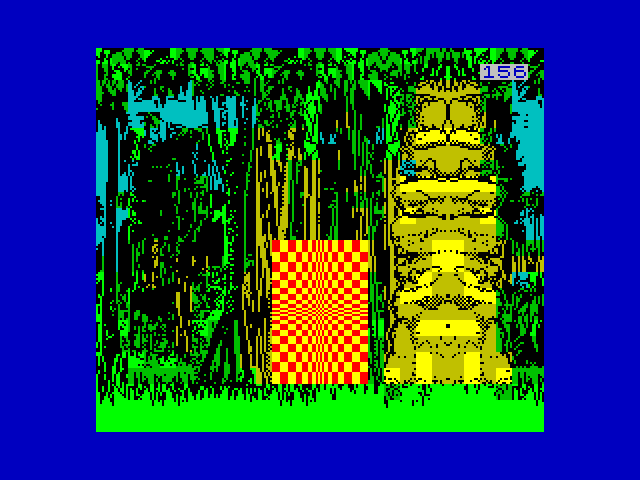

Explorer has a unique atmosphere, heightened by an unerring stillness throughout. Everything in this world is motionless except for the odd pool of water, and behind the dense forest lie hauntingly quiet villages, with strange stone totems towering over huts that have been abandoned by whatever used to live in them. Every so often, you encounter a shimmering warp gate — again, provenance unknown — that you can use to fly to a new area of oppressively empty wilderness. The only action is a sporadic (and clumsily implemented) attack by skittering bugs.

All this quiet beauty (a little phrase I’ve borrowed from Samantha Nelson’s very prescient article about World of Warcraft’s ghost cities), coupled with the focus on just walking around and discovering what’s over the horizon, makes Explorer something of a forgotten granddad in the exploration game family tree.

Yes, you could successfully argue that earlier first-person games — Mercenary, The Eidolon — created a similar atmosphere of exploring the unknown. But Relf and Dunstan’s game has a much deeper connection to today’s “walking simulators” (and by the way, I love Ed Keys’ point that if we’re going to deride exploration games on those terms, we should just go ahead and call FPSs “face clickers”).

Because Explorer was born from a literal walking simulator.

Two years before Explorer, Graham created The Forest, first for the TRS-80 and then for the Spectrum. It’s a game proudly described on its title screen as “a simulation of orienteering” — Graham created a full OS-style map for it — and it was probably the only 8-bit game ever deliberately built around the joy of walking. It got a rave review from Crash magazine, too. Explorer was, in Graham’s words, a “less orienteering-oriented version” of the same concept.

It’s fascinating to learn of Explorer’s orienteering heritage, then trek forward to today where Proteus is influenced by Ed Key’s childhood walks in the Wiltshire countryside and has a trailer filmed in the Lake District.

It’s just a shame that Explorer is, essentially, empty. There’s no reward for exploring — no puzzles like Myst, no story like Dear Esther, no enchanting you with colours and sounds and wondrous sights like Proteus. The eerieness of Explorer’s nameless planet, the empty buildings clearly once built and inhabited by something, suggest the beginnings of a mystery — but it’s actually the beginning and the end. There’s nothing to uncover. Just nine bits of spaceship and 39,999,999,991 empty locations.

As such, Explorer’s reviews were less than glowing. Still, it’s fun in retrospect to see game journalists of the ’80s as mystified by Explorer as many of today’s gamers are by genre-defying indie gems. Here’s Popular Computing Weekly’s verdict on Explorer:

[It] really does defy categorisation. It’s not an adventure, it’s certainly not an arcade game, and it’s too surreal to be a strategy game.

Sound familiar?

If Explorer had incorporated text adventure elements — probably the most fitting option in the era it was made — I suspect it’d have got better reviews, and moved it into the family tree of Myst (a game that both Proteus and Fract have often been compared to). And in fact, Explorer’s sketchbook look, and the lack of on-screen indicators and counters, lends it a similar atmosphere to ’80s graphic text adventures, which also often sent you alone into a foreboding forest or jungle (I’m reminded of the early stages of Activision’s 1985 adventure Mindshadow in particular).

Or perhaps if Graham and Simon had made Explorer a true sequel to The Forest, a proper walking game, just you and nature, with views that opened out rather than walls of rainforest that constantly closed in on you… well, it would probably have got even worse reviews. But as Tale of Tales told the VideoGameTourism site in response to all the “walking simulator” jibes about their games:

Walking is one of the nicest things one can do on this planet. Very worthy of simulation.

I’ve been in touch with Graham for this blog post — and after I contacted him, he’s started busily building a new version of The Forest in HTML! You can view the progress for yourself on Graham’s website.

Latest Comments